INTRODUCTION

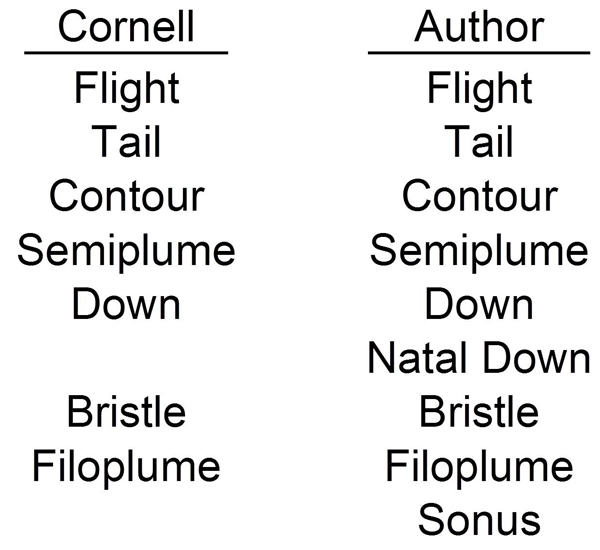

The top four google hits for “how many types of feathers do birds have” indicate a general lack of agreement, with Cornell Bird Academy citing 7, Bird Watching Daily and Study both having 6, and Bird Watching Academy 5. These numbers vary because they are overly simplistic, subjective groupings. In this article we ask: Does a feather look or have characteristics that differentiate it from others, and is it found in a significant population? Not all bird species have bristle feathers and some don’t have flight feathers.

Evolutionary adaptations within tail feathers like Twelve-wired Bird-of-Paradise vs. the stiff rectrix of a woodpecker or the serrated leading edge of an owl primary vs. an undifferentiated feather on a penguin’s wing are not separately categorized. Cornell lists seven basic feather types, this article identifies nine (Table 1).

table 1 feather listing

Flight Feathers

Flight feathers (remiges) are asymmetrical, with the leading edge being stiffer and narrower to prevent twisting as air flows over it. There are three groups – primaries, secondaries and tertiaries. Most birds have ten primaries counting from the inside to the end of the wing. The primaries provide thrust. There are 9-25 inner flight feathers or secondaries and are counted from the outside in. The secondaries provide lift. The inner most flight feathers are tertiaries and do not perform an essential part in flight. The wing feathers do not have an aftershaft or downy barbs that would hinder flight. Melanin is the pigment that makes feathers black. Black feathers are more resistant to wear and tear, thus many birds have black outer primaries.

Primary feathers are attached directly to the bird’s small, fused “hand” bones called the manus. All the rest of the feathers are attached only to the skin1.

There are many flight feather modifications such as the owl’s (Figure 1) serrated leading edge that dampens sound to maximize stealth. At the other extreme, penguins have no flight feathers at all.

figure 01 serrated edge

Tail feathers

Tail feathers (rectrices) are variable, with most birds having 12. Hummingbirds have 10 and other species range from 6 to 32 (Figure 2). The feathers are arranged in a fan like structure and counted from inside out. The outer feathers are more asymmetrical than the inner ones. They have the same microstructure as the flight feathers and are used for steering.

Figure 2 (left) Immature Cooper’s Hawks (the smaller male is left of the female on the right). (right) Rufous Hummingbird

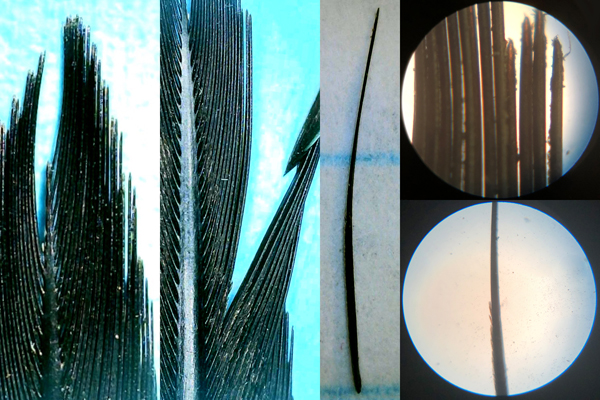

There are many exceptions to the standard tail, the starkest of which is the Twelve-wired Bird-of-Paradise. While processing feathers from a Gila Woodpecker, I noticed some interesting morphology. The barbs at about a third of the distal end of the tail were very stiff and lacked barbules, much like a plastic toothpick (Figure 3). The barbs gradually had more and more barbules till about halfway towards the proximal end, the barbs displayed normal pennaceous structures. The stiffness of the barbs supplants the need for hooklets to keep them in place. The barbs can move independently, much like a 3D contour gauge (a row of pins that conform to the shape of an object). This feature assists a woodpecker with locomotion, hanging from a vertical or angled branch, and stabilizes the woodpecker when hammering.

Figure 3 Gila Woodpecker rectrix detail

Contour Feathers

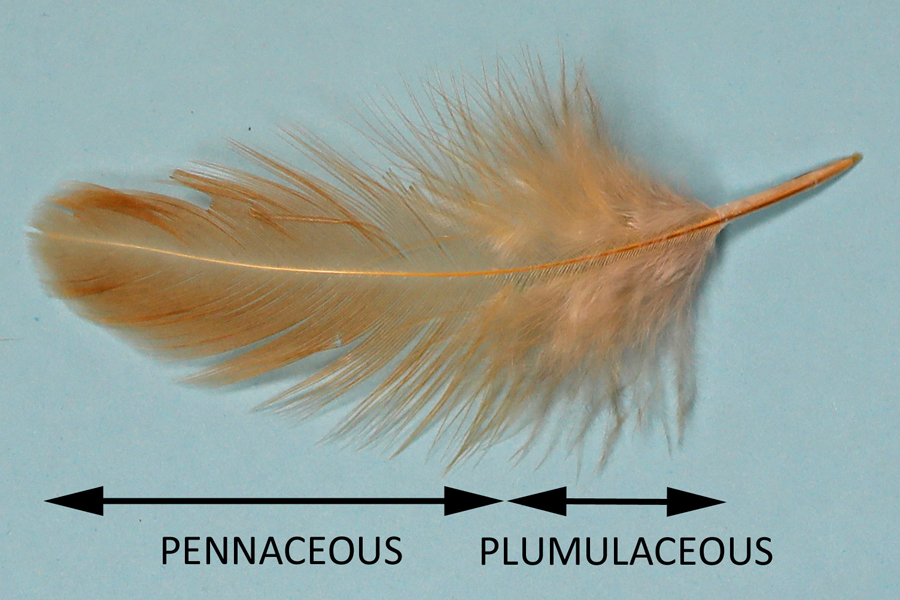

Contour feathers (Figure 4) cover the entire body and are typically symmetrical. The aftershaft length is variable, with the shortest being on the wing to minimize airflow disruption. The downy barbs are close to the body. The feathers are overlaid like shingles which waterproofs the bird. Contour feathers that cover the base of flight feathers and above and below the base of the tail are called coverts.

Figure 4 Chicken contour feather

Figure 5 Various names for contour feathers, depending on their location. (clockwise from top left) Red Junglefowl hackle feathers are on their necks, tail coverts on a Yellow-rumped Warbler, Turkey Vulture axillaries in the axilla (“armpit”), and lores in front of the eyes on a White-eyed Vireo are just a few of the many contour feathers.

Afterfeather (hypopnea) are a secondary feather growing from the dorsal side of a contour feather. It emerges at the base of the vane. The barbs are plumulaceous that sometimes attach to a rachis. Their appearance is like a downy feather and serves the same purpose.

Peregrine Falcon breast contour feather with afterfeather

Semiplume feathers

Semiplume feathers (figure 6) are a cross between downy and contour feathers. Unlike downy feathers, they have a long rachis with a long aftershaft section containing barbs with underdeveloped hooklets. These feathers are disbursed under the contour feathers for insulation.

Figure 6 Semiplume feather

Down Feathers

Down feathers (plumule) are the closest feathers to the body and not exposed to the elements. The barbs are without hooks, allowing for a chaotic distribution and insulation (Figure 7). Down feathers have little to no rachis, are relatively short, and have spaced, flexible barbs without hooklets. Feathers found in amber indicate that some dinosaurs were covered by them. The body down feather has been used by humans for insulation in clothing and bedding as far back as 200,000 years. Many birds use their body down feathers and those of others to line their nests.

Figure 7 Down feather

Some species’ down feathers produce powder (figure 8 right). Powder down feathers (pulviplumes) are found on herons, pigeons, tinamous, bustards, and parrots. The tips of the barbules disintegrate creating a talcum like keratinous powder. These feathers never molt. A second kind of powder down creates the powder from cells that surround the barbules of growing feathers. The powder is used for preening and waterproofing.

Figure 8 Natal down on Tri-colored Heron (left) and powder down dust from a dove window strike (right)

Natal Down Feathers

Young birds are covered in natal down feathers (Figure 8 left). Precocial nestlings from ducks and quail are born with them, altricial chicks develop natal down feathers within 6 days of hatching.

Figure 9 Ring-necked Pheasant (top) chicken (center) filoplumes, human hair (bottom)

Filoplume Feathers

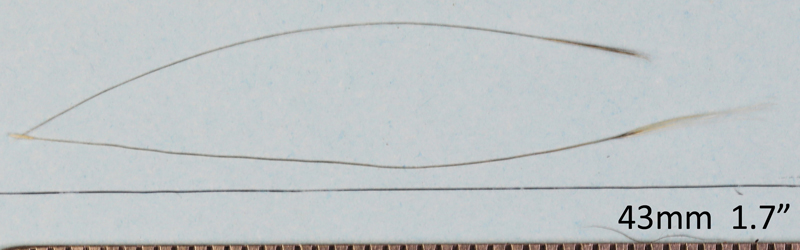

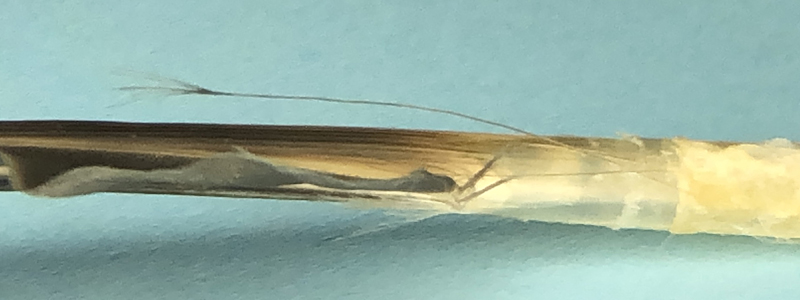

Filoplume feathers, the third feather structure, have a short calamus and a long, bare rachis that ends with a small tuft of barbs. Figure 9 compares filoplumes to a human hair. Filoplumes come in varying lengths depending on their location. They are found under contour feathers, with a heavy concentration around flight feathers (Figure 10). They are attached to sensory receptors in the skin that detect air pressure, wind and feather movement. Every bird has at least one filoplume per wing, tail or body feather. Flight feathers have up to 12 filoplumes each.2

While handling a chicken flight feather, I noticed a filoplume. On closer inspection, there were five.

Figure 10 Filoplume on flight feather

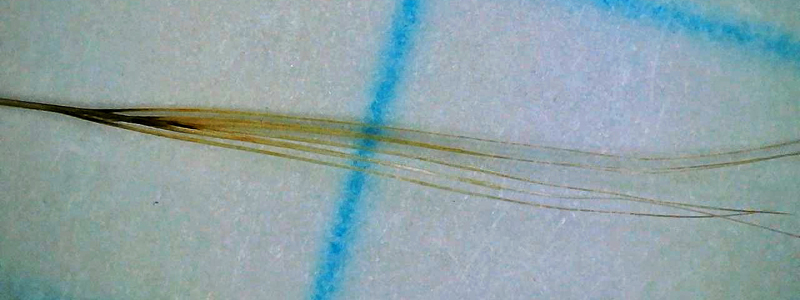

There are no barbules or hooklets on this small tuft of barbs (Figure 11). Some internet illustrations of filoplumes show barbules. Plucked chickens’ residual filoplumes are so numerous it is recommended to singe them off.

Figure 11 Filoplume tuft

Bristle Feathers

Figure 12 Species with bristle feathers (clockwise from top left) Say’s Phoebe, Greater Roadrunner, Emu, Great Horned Owl, Plain Chachalaca, and Pyrrhuloxia.

Bristle feathers are found on many species. Bristles are whisker-like feathers typically found around the mouth, eyelids and nares. Bristle feathers maybe unbranched or branched. The branched bristles can have minimum barbs at the base to more elaborate structures as found on nightjars. Some birds have both types of structures as shown in figure 13. Bristles are sensitive to touch and vibrations. They assist in foraging and obstacle avoidance, protect from airborne particles, and sense airflow. Some sites state that bristles are used to funnel food. That was dispelled in an article about Willow Flycatcher bristles.3

Figure 13 Harris’s Hawk bristle feathers

Sonus Feathers

Auriculars are ear coverts, feathers that cover the ear opening called the meatus. Auriculars are not on any feather type list but are grouped with contour feathers. Not all birds have auriculars such as the Turkey Vulture and Wood Stork.

Auriculars come in two types, bristle feathers as found on ostriches and sonus feathers (author’s term) found on the vast majority of bird species. Some birds, like the American Kestrel, have a combination of the two types as shown in figure 14.

Figure 14 American Kestrel auriculars, sonus (left) bristle (right)

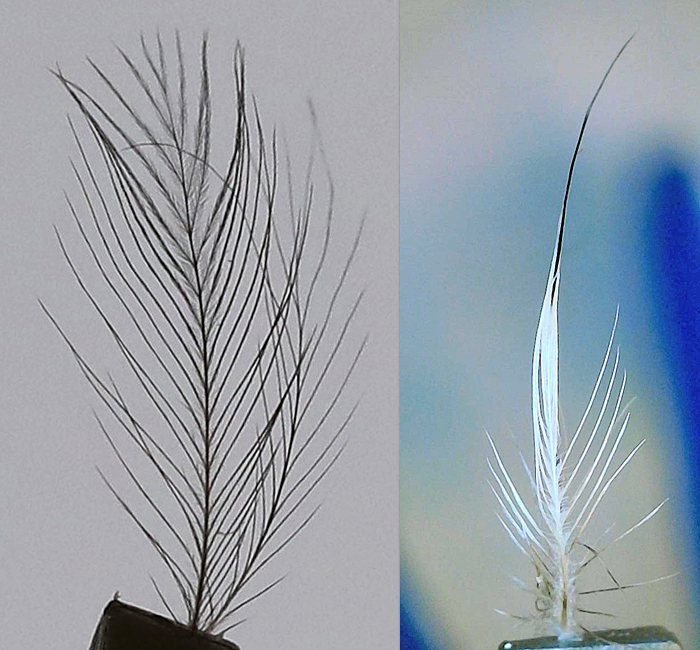

Sonus feathers have a long stiff rachis with well-spaced barbs. The barbs have stiff rami with few if any barbules that are void of hooklets. The vane is airy, allowing for sound to pass. The Ring-necked Pheasant sonus on the left in Figure 15 is one inch long. Unlike down feather barbs, sonus barbs hold their shape.

Figure 15 Ringed-neck Pheasant (left) and chicken (right) soni

Table 2 shows attributes of various feather types. The sonus feather does not fit any of the standard feather structures.

Table 2 Summary of feather attributes

The two examples in Figure 15 show a fanned out pattern which is due to static electricity. Figure 16 shows sonus feathers covering the meatus. Note the barbs are in a naturally compressed helping to repel dirt and water.

Figure 16 Chukar (left), Harris’s Hawk (center), and Gamble’s Quail (right) auriculars

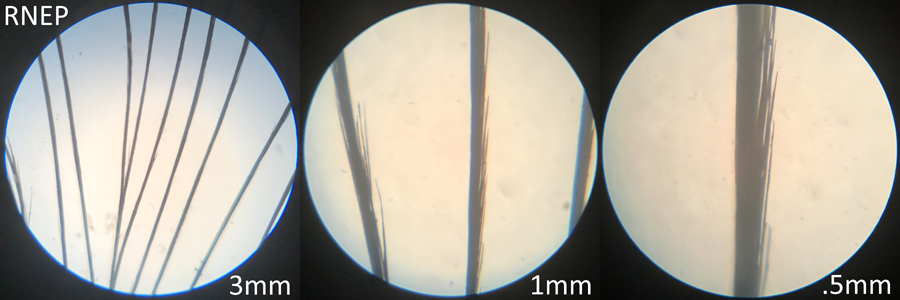

Figure 17 shows a Ring-necked Pheasant sonus magnified 50, 150 & 300x. Note the absence of barbules and associated hooklets. This design minimizes sound interference.

Figure 17 Ring-necked Pheasant sonus

Other than a Barn Owl auricular study, there is little to no information on this feather type. Seeing these feathers in my photography I decided to do an in-depth study of them. Preliminary results are very exciting and will be the basis for coming articles.

1Phillipsen, Ivan. (2020) The Parts of a Feather and How Feathers Work. “https://www.scienceofbirds.com/blog/the- parts-of-a-feather-and-how-feathers-work”

2Devokaitis, Marc (2020) The Most Mysterious Feather: Filoplumes. Cornell “https://www.allaboutbirds.org/news/the- most-mysterious-feather-filoplumes/#”

3Conover, Michael R. and Miller, Don E. (1980) Rictal Bristle Function in Willow Flycatcher. The Condor, Vol. 82, No. 4, pp. 469-471